| From The Lamanai Ruins To The San Pedro Lagoon - |

| Ooh, La, La! Shelling In The Belize Experience |

| By Karen VanderVen |

As a die-hard sheller, when I am on a trip, I

want to be in the water as much as possible doing you-know-what. On a recent

trip to Belize, Central America, I became a believer also in lifting my head

upward from the beaches and bottoms long enough so as to experience the country

a bit - its history and natural features. Of course, the fact that visits to a

variety of shelling habitats in this tropical land were also in the offing made

this trip a "must - do". Thanks to my ever- forbearing husband who,

when he heard that there would be a visit to Mayan ruins included and wanting me

to broaden my horizons, encouraged me to go. As a die-hard sheller, when I am on a trip, I

want to be in the water as much as possible doing you-know-what. On a recent

trip to Belize, Central America, I became a believer also in lifting my head

upward from the beaches and bottoms long enough so as to experience the country

a bit - its history and natural features. Of course, the fact that visits to a

variety of shelling habitats in this tropical land were also in the offing made

this trip a "must - do". Thanks to my ever- forbearing husband who,

when he heard that there would be a visit to Mayan ruins included and wanting me

to broaden my horizons, encouraged me to go.The odyssey began in Miami as Peggy Williams, trip leader, shepherded her flock of six together to check-in. Soon Joe and Betsy Johnston from North Carolina, Dot Kierstead and Yvonne Lloyd from Florida, Brig Alexander and myself from Pittsburgh, along with Peggy, were on the plane for the flight two hours southwest and, passing two time zones, two hours earlier. Crossing the Florida Keys, Cuba and Cozumel, before we knew it we had landed in Belize City. It’s A Jungle Out There After settling into our very pleasant tropical style hotel, we were in a van headed south to the famous Belize Zoo, where the animals are uncaged in a natural jungle setting. Jaguars, snakes (including non-venemous boa and deadly fer-de-lance), birds, crocodiles, the famous jabiru storks all engaged our attention. We would have to approach an area identified as the habitat of a given animal and quietly wait for it to show itself by noise or movement. Most captivating to me was a little otter or "river dog" who dove backwards into its pool, swiftly swam underwater to suddenly surface right in front of me, pop up out of the water, and plop back in to repeat the process. The next day, we were up early to drive up to the town of Orange Walk, our embarkation point for the jungle boat trip down the New River about 20 miles to Lamanai, a Mayan ruin. Fitted out safari-style with hats and binoculars and sitting comfortably in the open boat, we were entranced by the winding curves of the river, the thick tropical palms and other trees, tannin-stained quiescent brown water, and flowered lily pads upon which exotic birds lit. As we moved down the New River, I marveled to my boat mates - "Two days ago Pittsburgh - today the jungle." I had never felt so far from home in such a joyful way. We stopped to search for unusual and grayish hard-to-spot boat-billed herons in the dense foliage, with finally each person in the boat-filled harem was able to get a glimpse of the birds. For the birders, among the bird species spotted and identified were jacana, wood stork, purple gallinule, snowy egret, ring-necked kingfisher, cormorant, mangrove swallow, kiskadee flycatcher, snail eating kite, toucan, and little green heron. I’m sure those keeping their birding "life lists" got some additions. Upon arrival at the developed clearing with a choice of souvenir shops that was the entry point to the ruins, we were served a delicious traditional Belizean lunch, including red beans, rice, plantains, and boiled spicy chicken. Then our guide came forth to take us first to an artifact filled museum and then on to the ruins. He had the knowledge and the vocabulary of an Oxford professor as he explained their history and structure in great detail to a neck-stretching audience as we gazed to the top of these huge structures. I decided to climb to the top for a photo of me gazing up at the sky to show my husband that yes - I went to the Mayan ruins - this was not just another of my eternal trips focused on only shells and always looking down. Before the tour was over, the most ardent shellers had a chance to follow their collectors’ instincts: there were beautiful round, dark striped large fresh water apple snails on the lagoon shore and land snails on the trails to the ruins. The next day we boarded a plane at a tiny airport to fly to San Pedro, the town at the southern tip of Ambergris Cay. Before long we were in a guide-driven boat, racing across cobalt blue offshore waters, eager for our first plunge for shelling. There’s The Reef We spent two days of shelling at different spots right inside the barrier reef, where a wide range of species was found. This was enhanced by the fact that the habitat was varied. There were areas with rocks and slabs to turn, strips and patches of sand to fan, and beds of grass to scan.

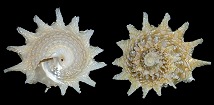

On our second day at another reef spot, what one didn’t find for oneself, our guide, Mech, did. We got back in the boat to find that while we shelled, our native guide used his intimate knowledge of the area to bring back some treats for us. These included a stunning orange-rayed pair of Laciolina laevigata (Linnaeus, 1758) [Smooth Tellin], a perfect Lobatus gigas (Linnaeus, 1758) [Queen Conch], a fine Lobatus raninus (Gmelin, 1791) [Hawkwing Conch]; a Lobatus costatus Gmelin, 1791 [Milk Conch] (whose aperture was bright red rather than the usual grayish white - a very unusual shell); a huge live Cassis madagascarensis Lamarck, 1822 [Cameo Helmet]. and, every sheller’s dream, a Lobatus gallus (Linnaeus, 1758) [Roostertail Conch]. These were parceled out faster than an angry tulip snaps at a collector’s grasping hand. Incredibly, each of us got the particular shell we craved, in my case the Smooth Tellin. Tellins are one of my favorite species and this will certainly be a centerpiece of my tellin collection. Collectively, there was a multiplicity of interesting species taken on the reef side of the cay including (besides the shells already mentioned): Tellinella listeri (Röding, 1798) [Speckled Tellin], Jonhsonella fausta (Pulteney, 1799) [Favored Tellin], Barbatia domingensis (Lamarck, 1819) [Red-brown Ark], Ctenoides scaber (Born, 1778) [Rough Fileclam] and Limaria pellucida (C. B. Adams, 1846) [Antillean Fileclam], Caribachlamys pellucens (Linnaeus, 1758) [Knobby Scallop], C. sentis (Reeve, 1853) [Scaly Scallop], and C. ornata (Lamarck, 1819) [Ornate Scallop]; Neotiara nodulosa (Gmelin, 1791) [Beaded Miter], Probata barbadensis (Gmelin, 1791) [Barbados Miter], Trachypollia nodulosa (C. B. Adams, 1845) [Blackberry Drupe], Dulcerana cubaniana (d'Orbigny, 1847) [Granular Frogsnail], Vasum muricatum (Born, 1778) [Caribbean Vase], Talparia cinerea (Gmelin, 1791) [Atlantic Gray Cowrie], Erosaria acicularis (Gmelin, 1791) [Atlantic Yellow Cowrie], Tegula fasciata (Born, 1778) [Silky Tegula], Bailya intricata (Dall, 1884) [Intricate Phos], Volvaria avena (Kiener, 1834) [Orange-band Marginella], Diodora minuta (Lamarck, 1822) [Dwarf Keyhole Limpet], Tonna pennata (Mørch, 1852) [Atlantic Partridge Tun], Engina turbinella (Kiener, 1835) [White-spot Engina], Arene cruentata (Mühlfeld, 1829) [Star Cyclostreme], Lithopoma tectum ([Lightfoot], 1786) [West Indian Starsnail], Cymatium nicobaricum (Röding, 1798) [Goldmouth Triton], Cassis tuberosa (Linnaeus, 1758) [Caribbean Helmet], Cassis flammea (Linnaeus, 1758) [Flame Helmet], Cyphoma gibbosum (Linnaeus, 1758) [Flamingo Tongue], Phyllonotus pomum (Gmelin, 1791) [Apple Murex], Pinna carnea Gmelin, 1791 [Amber Penshell], Prunum guttatatum (Dillwyn, 1817) [White-spot Marginella], P. apicinum (Menke, 1828) [Common Atlantic Marginella], Cerithium guinaicum Philippi, 1849 [Guinea Cerith], C. litteratum (Born, 1778) [Stocky Cerith], C. lutosum Menke, 1829 [Variable Cerith], Morum oniscus (Linnaeus, 1767) [Atlantic Morum], Tracypollia turricula (von Maltzan, 1884) [Twin Drupe], Conus jaspideus Gmelin, 1791 [Jasper Cone], Leucozonia nassa (Gmelin, 1791) [Chestnut Latirus], Teralatirus cayohuesonicus (G. B. Sowerby III, 1878) [Key West Latirus], Zebina browniana (d’Orbigny, 1842) [Smooth Risso], Naticarius canrena (Linnaeus, 1758) [Colorful Moonsnail], Hipponix antiquatus (Linnaeus, 1767) [White Hoofsnail]. Of note were the large and beautiful Barbados Miters and the Scaly Scallop that was dark purple - almost black. A tiny turrid, Daphnella lymneiformis (Kiener, 1840) [Volute Daphnelle], found on the underside of a rock and barely visible, was a special treat for me. Not Blue On The Lagoon Two other days we were ferried through channels connecting the ocean to the bay side to shell in the lagoons created by the curving terrain. This turned out to be a fascinating area and one filled with new species to be collected. The main focus, the shell everybody wanted to find, was the elegant gray, long tailed, spinose murex Vokesimurex messorius (G. B. Sowerby II, 1841) [Messorius Murex]. On my first day, I patted every perturbation, fanned every spot in the sand, checked out every rocky cavity, and threaded my hand through the mossy grass in search of a specimen. No luck. So I sadly gave up and concentrated on what I was finding. And I was in no way unhappy with the fine live Melongena melongena (Linnaeus, 1758) [West-Indian Crown Conch] along with gorgeous multi-colored and sized Fasciolaria tulipa (Linnaeus, 1758) [True Tulip] that were turning up. I heard voices over the water calling - "Karen, Peggy has something for you!" Like a lone shark suddenly sensing a bucket of chum, I zoomed over to Peggy who pointed in the water in front of her so that I could take the shell below. Soon the just visible little gray under water lump was in my hand - a fine Messorius Murex. "Self-collected" at that! To add to the varied-colored and -patterned medium sized tulip specimens I found, Yvonne gave me a huge one she found which will definitely contribute to the tulip exhibit I am trying to put together for a shell show. It occurred to me that the quantity of these, and the fact there were no live ones seen, could be related to Hurricane Keith. This destructive storm, which blew through Belize in October, 2000 from the west sparing the oceanside reef, could have wreaked havoc on the lagoon side, such as killing the tulips. There were other shells as well: Cerithium litteratum (Born, 1778) [Stocky Cerith], Lampanella minima (Gmelin, 1791) [West Indian False Cerith], and a variety of bivalves: Scapharca brasiliana (Lamarck, 1819) [Incongrous Ark], Chione cancellata (Linnaeus, 1767) [Cross-barred Venus], Serratina aequistriata (Say, 1824)[Striate Tellin], Laevicardium mortoni (Conrad, 1830) [Yellow Eggcockle], and even pairs of Anomia simplex d’Orbigny, 1853 [Common Jingle]. I found just one pair of a beautiful greenish striped oyster, Pinctada imbricata imbricata Röding, 1798 [Atlantic Pearl-oyster], which Peggy also found alive on the turtle grass. On a subsequent trip to the lagoon, I found several Messorius Murex on top of the sand. Curious as to why on one day they were buried and hard to spot, and readily visible another day, Peggy explained that the sand in one area was deeper before the rocky substrate was reached, so that the shell couldn’t bury itself so far. While shelling this day, she called us all to swim over for a special treat. As she later described it "We were privileged to watch Messorius Murex laying eggs in a communal clump - in San Pedro Lagoon in about four feet of water. There were several Murex in the area, some heading for the clump and some away (finished?) Some were moving very actively. The clump was about 8 inches across at that time and there were about six animals still laying. It was loose in a depression in the sand." We all gazed at this display and then carefully swam off. Searching For The Lost Colony On the way to another part of lagoon on another afternoon, we tried to locate an ostensible colony of Strombus pugilis Linnaeus, 1758 [West Indian Fighting Conch] that lived offshore on the southern part of the cay. To aid us in spotting them, Peggy and I were towed on long ropes on the back of the boat. The experience was akin to water skiing on one’s abdomen and I could even slalom back and forth to extend my view. I smiled to myself as I thought of the numerous methods people used to collect shells and the fact that we were using many of them on this trip. Unfortunately the conchs eluded us, for this trip anyway but those of us who really wanted a few specimens were able to buy them from a souvenir store down the street from our hotel. Home, a bit of additional cleaning, oiling, and placement in a specimen box have made these quite attractive It's An Ill Wind That Blows Nobody Good This old proverb applied well to our last day. We had hoped to take a day trip with a picnic to a spot where the reef comes in close to the shoreline. Sipping my early morning coffee on the porch, I periodically put my mystery novel down long enough to realize that whitecaps, flapping flags and bending palms before me indicated too-rough weather for an oceanside boat ride. "Trade winds", I harrumphed to myself. "I guess so - they certainly suppress the dive trade". I contemplated a day in the San Pedro Internet Cafe. However, Peggy quickly concocted an alternate plan for the day: Ride in golf carts to the ferry to the north shore of the island, cross, check out any beaches we wanted, and have lunch. Brig decided to opt for a snorkel trip to swim with sharks. Joe and Peggy took the helms of the carts and adroitly piloted the rest of us down the busy main street. We rolled up onto the quaint but utilitarian rope-pulled ferry across the channel separating the southern from northern part of the cay, and soon we found our first beach area - and shells. Many shells. This was probably the best beach shelling I have ever experienced - perhaps even rivaling Sanibel Island in its hey-day before the causeway was built. In the seaweed demarcated tide line were fine pairs of solidly colored bright yellow Phacoides pectinatus (Gmelin, 1791) [Thick Lucine] in a range of sizes. These were absolutely stunning and ennoble this humble and common family. They were also a refreshing break for this Pennsylvanian from the eternal Lucina pensylvanica (Linnaeus, 1758) [Pennsylvania Lucine], whose dreary shells seem to be abundant in spots where otherwise there is nothing. I ventured up further onto land where offshore sand was being piped up in a dredging operation and found a pair of Favored Tellins with the demised animal still inside. We’ve all found lots of perfectly fine pairs of this common shell all over the Bahamas. After cleaning, however, this turned out to be more than your usual ho-hum pair of clams. In perfect condition and hinged, each yellow valve is sharply bordered at the edge by pure white. Other bivalves included purple-brownish marsh clams (Polymesoda species), Codakia orbicularis (Linnaeus, 1758) [Tiger Lucine], Tucetona pectinata (Gmelin, 1791) [Comb Bittersweet], and Cucullaearca candida (Helbling, 1779) [White-beard Ark] - more attractive than you might think. In the univalve department, it was "Marginella Mecca". Fine specimens of Prunum guttatum (Dillwyn, 1817) [White-spot Marginella] and P. oblongum (Swainson, 1829) [Oblong Marginella] - right on the shore, if you can believe; P. apicinum (Menke, 1828) [Common Atlantic Marginella], and another species of marginellid, yellow and slender, that Peggy recognized as different from the others that were found. Lithopoma phoebium (Röding, 1798) [Longspine Starsnail] were abundant although these, truth to tell, had seen better days. There were Bulla occidentalis A. Adams, 1850 [Striate Bubble], a dead but decent Cypraeacassis testiculus (Linnaeus, 1758), [Reticulate Cowrie-Helmet], and absolutely miniscule dark orange tulips. We found two species of Columbella - Columbella mercatoria (Linnaeus, 1758) [West Indian Dovesnail] and Columbella dysoni Reeve, 1859 [Dyson’s Dovesnail]. Peggy showed me how to discriminate between the two. The latter, which I had never collected before, are more narrow and elongated than the West Indian Dovesnails, and the little brown markings make these very handsome little shells. There were numerous tiny species, including Neritina, Cerithideopsis costata (da Costa, 1778) [Costate Hornsnail], Niveria quadripunctata (J. E. Gray, 1827) [Four-spot Trivia], and even one Smaragdia viridis (Linnaeus, 1758) [Emerald Nerite], some Caribbean periwinkle species, Littoraria nebulosa (Lamarck, 1822) [Cloudy Periwinkle] and L. angulifera (Lamarck, 1822) [Mangrove Periwinkle]. As I marveled later at my finds of several new species I had never before collected anywhere, it occurred to me that that the whole day had a magical quality about it and that the winds had blown good fortune unexpectedly our way. Just one more feature of shelling - you just never know when you are going to get a very pleasant surprise. Brig had a great time mingling with the rays and sharks - and so a good time was had by all! Can You Belize It? This clever saying seen on T-shirts in the souvenir shops reflects to me two things: the charm and delightful ambiance of Ambergris Cay, and the very pleasant "living" that is characteristic of it. (In fact, a recent study named Ambergris Cay as one of the top retirement spots in the world). Certainly my preconceived beliefs about what I might expect in a tropical Central American country were punctured by my Belize experience. For this trip, anyway, all the cautionary tales heard beforehand about challenges of trips to tropical countries, and undoubtedly embellished in one’s mind, about torrents of rain leaving muddy puddles, swarms of mosquitoes diving for exposed skin, water of questionable drinking quality, and oppressive heat were unsubstantiated. I, for one, didn’t get as much as a mosquito bite; there wasn’t a drop of rain, and there was either drinkable or bottled water available everywhere. While the brisk trade winds that blew our European forebears over the ocean to the New World made for some rough water around the reef, undoubtedly it also contributed to the pleasant temperature and blew the bugs off. We all did enjoy the little iguana that took a stroll through the sand right in front of our porches. To be prepared for any medical contingency, I had assembled, before leaving Pittsburgh, a complete pharmacopoeia into a homemade medicine kit to cover any health contingency. I was even prepared to do dental repairs. The kit wasn’t needed both because nobody got sick and also because the local supermarket had a drug counter as big and well stocked as any in an American chain. As for food, we got better and better at scoping the restaurants in San Pedro. Dot and Yvonne found a restaurant where residents ate in the morning and I enjoyed a substantial breakfast there with them one morning while chatting informally - and the food beat my usual mundane cold cereal and juice. We loved the little deli near the hotel where we could get a quick hot dog for lunch. We had several delightful and tasty evening meals at restaurants with sand floors serving tasty and well prepared meals of chicken and fresh fish. I’ve had few lunches as delicious as the one served at a restaurant called "Sweet Basil" on our last day. Several of us topped off our meals with hot fudge sundaes that energized us for the rest of the day’s shelling. Our compatible group enjoyed strolling up and down the sandy streets of San Pedro, filled with enticing souvenir shops, and striking up conversations with the residents. Native San Pedroans seem to like basketball as much as I do (after shells, that is). One night I enjoyed insinuating myself into a shoot-around on an off-street court, dribbling the ball around a surprised defender (nobody is used to a ‘mature’ lady driving her way to the hoop and doing a pump fake) and praying that her shot would go in (it did!) We posed for photographs here and there - in restaurants, on the boat dock, and once Betsy, camera in hand, had importuned us to " Say Belize" so that we’d smile widely, it was easy to let our good times and spirits be recorded for posterity. And they didn’t end right up until the last minute. Shells continued to come our way. As we were packing the last morning, one of our shelling guides, Mech, came by bearing two spectacular shells: a stunningly-marked Charonia variegata (Lamarck, 1816) [Atlantic Trumpet Triton] and a fine large Cameo helmet. They were gifts for our group and the only question was - how would it be decided which shellers would take home these treasures in their shell bags? We quickly set up an auction process, and the drawing took place for those who wanted to participate. Dot won the triton, and Brig, the helmet. In the meantime that last morning a very special event occurred that gave me just one more very warm memory to take away. On our very first day in Belize, I had walked down to the dive shop on the dock in front of our hotel and had gone in to get acquainted. I noticed a tray on the counter of beautiful shells that had been found on its dive trips. There were Calliostoma javanicum (Lamarck, 1822) [Chocolate-line Topsnail], Roostertail Conchs, and setting me to gaping, a fine Linnaeus, 1758 [Glory-of-the-Atlantic Cone]. I admired the shells and offered to buy the cone, saying that it was a rare shell and that I’d offer an appropriate price for it. "Not for sale!" I was told. It was kept there to show prospective divers. Because of the winds, as mentioned, there had been no scuba diving for me or anyone else, and I wondered about the negative impact on the dive shops’ business. On the last day, I went in again and decided at least to buy one of their attractive T-shirts with a drawing of the "Mayan God of Scuba Diving" even though usually I don’t buy a dive shirt unless I’ve actually dived with the outfit. As the young woman placed my shirt in a bag, she reached over to the tray and handing me the Glory-of-the-Atlantic Cone said "I remember that you like this shell. I’d like to give it to you". I offered again to buy it, but she emphatically said "no". I couldn’t Belize this generous gift. I will certainly always remember it, especially as I glance over at the colorful orange and brown cone right here in a box with a deep blue lining. By the end of the day, on an uneventful flight, we were back in Miami, and dispersed back to our homes - but with gorgeous and bountiful shells, and memories of the Belize experience, to connect us for a long time to come. |