| Immigrant Mussel Settles In Northside Generator | |

| By Harry G. Lee | |

| Monday mornings are generally hectic where I work - lots of business accumulating over the weekend. Consequently, on October 20, 1986 I was almost forced to have one of my coworkers take a message from the Jacksonville Electric Authority's (JEA) Bob Kappelman, but the word "clam" was mentioned, and curiosity prevailed. Bob, an engineer, was referred by the Marine Science Center's Charlotte Lloyd, whom he called because inch-long clams were found in the cooling system of the Northside Generator. These critters occurred in substantial concentrations, especially on filters designed to exclude large particles (such as eels and crabs) from fouling the delicate network of pipes in the steam condensers. Bob described a curved, elongate clam - not characteristic of the culprit I had expected (and he had read about), the Asiatic Clam. Corbicula fluminea (Müller, 1774), as it is called, has a remarkable and much-maligned penchant for clogging manmade freshwater channels such as irrigation pipes. Shortly Bob convinced me that the Asiatic immigrant was not guilty when he said the source of the incoming coolant was the St. Johns River near Blount Island. This locality would provide water too high in salt content for that species' survival. | |

|

Figure 1

|

|

| Later that day I was able to examine two specimens, which were clearly unlike any shells I or any member of the Jacksonville Shell Club (to my knowledge) had ever collected in the U.S.A. The shells were translucent, basically yellowish "mussels" with faint purplish zigzags over the dorsal and posterior (left in fig. 1) aspects. Their shape was nearly identical to the Blue Mussel - Mytilus edulis (Linné, 1758), which occasionally visits Jacksonville as a stowaway in driftwood, etc., but does not survive our torrid summers (fig. 1 shows M. edulis on the right, and the JEA mussel on the left along with a millimeter scale). The latter was clearly not among the "mussels" known to occur in the St. Johns River (nor on the checklist of Northeast Florida maintained by the Jacksonville Shell Club). These are Conrad's False Mussel - Mytilopsis leucophaeata (Conrad, 1831), which has a dull coating of periostracum and a different hinge structure; the Ribbed Mussel - Geukensia demissa (Dillwyn, 1817), which does not belie its cognomen, having prominent longitudinal ribs; the Hooked Mussel - Ischadiurn recurvum (Rafinesque, 1820); and the Scorched Mussel - Brachidontes exustus (Linné, 1758). Both of the latter two are also prominently ribbed. | |

|

|

|

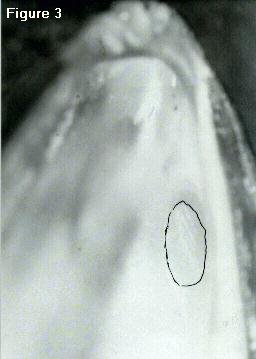

That night the JEA shells were examined under the microscope, and their true identity became apparent - well, almost. Figs. 2 and 3 show inch-long JEA and Blue Mussels respectively. Each is magnified 30 times. The inside of the beak is at the top of the picture and bears a few small teeth in each case. On the right-hand side of each photo is a (slightly retouched) scar representing the attachment of the byssal retractor muscle, which pulls the mussel closer to its holdfast on the substrate. The scar is deeper, longer, more irregular and further from the beak in the Blue Mussel (fig. 3). It is smooth, simple, smaller and circular in the JEA mussel (fig. 2). This difference is consistent and at present the main basis for separating the genus of the Blue Mussel, Mytilus, from Mytella Soot-Ryen, 1955. Thus we had a generic name with which to operate. There are thankfully few described species in Mytella. After consulting several popular books, I determined that the shells were those of a species found from Venezuela to Argentina as well as in tropical western America, where its occurrence appears to be more sporadic. Names employed in various books included M. strigata (Hanley, 1843), M. falcata (d'Orbigny, 1846), and M. charruana (d'Orbigny, l846). Myra Keen (1971) noted that falcata was not available for our shell because the name had been used earlier by Goldfuss (for a different critter altogether). With the list pared to two candidates, I spoke with mussel expert, Dr. Ruth Turner of Harvard's Museum of Comparative Zoology. She confirmed my identification and further commented that M. strigata was not clearly described and, unless location and examination of the type material (Hanley's original shell or shells) was made, the name would not stand. Thus, until some scientist clarifies the situation, the best name for the JEA mussel is Mytella charruana (d'Orbigny, 1846), which we might call the "Charrua Mussel!" Name notwithstanding, it was clear we were dealing with a recently-introduced exotic species. Authorities need to be aware of such imports, which are seldom desirable and may prove disastrous - cases in point the Asiatic Clam, Water Hyacinth, and Gypsy Moths - so I notified the Florida State Museum, the Game and Freshwater Fish Commission (Florida Dept. of Natural Resources), and the Jacksonville office of the Florida Dept. of Environmental Regulation, where I spoke with Larry Eaton, an environmental engineer, who reported first-hand an experience similar to the JEA situation with Paper Mussels - Arcuatula papyria (Conrad, 1846) in the Sarasota area not long ago. On Saturday, October 25th, Charlotte Lloyd and I visited Plant Engineer Bob Lucas at the JEA's Northside Generating Station. He acquainted us with the general operation of the facility and the basic principles of electrical generation. Regardless of the energy source, any generator is inefficient to the point that heat is wasted and MUST be controlled. That is where the cooling system enters the operation. At Northside fuel oil is burned to boil water and the steam turns the turbines, which create electricity by friction. The steam is still plenty hot after it sees the turbine and must be recovered (it is high-quality distilled and de-ionized water). This cooling/reclamation is accomplished by a condenser 28 feet high and nearly the same in diameter. Through it pass 21,000 pipes made of a special copper-nickel alloy - each about an inch in diameter and the group carrying 140,000 gallons of St. Johns River water each minute of operation. The steam passes downward through the myriad columns and rows of pipes and eventually condenses. The operation is like a reversed automobile radiator - the coolant is heated and discarded instead of being cooled and retained. When you consider we were inspecting Northside 3 - there being two nearly identical twins nearby on campus, you get a good idea of the importance of water and its proper delivery to the condensers. Any significant obstruction to flow could be costly - not particularly to the plant's safe operation, but to the environment. Regulations keep the amount of heating of ambient water to three degrees Fahrenheit. |

|

|

Figure 4 |

Figure 5 |

|

|

|

This is where the mussel infestation enters the picture. Bob showed us (figs. 4 and 5) a fouled filter removed earlier that day from an inbound pipe only a few feet from the condenser. Fortunately the pipe walls were spared by the molluscan invaders. You can see how the tenacious mussels have attached to most of the available surface of the filter and have withstood a flow of several feet per second. If the mussels weren't removed at regular intervals - intervals determined by THEIR numbers and rate of growth at present, overheating might occur. The present solution seems to be effective, and we expect that the cooler months will bring an abatement. Whether the future will produce a spontaneous disappearance (as was the case with Larry Eaton's Paper Mussels in Sarasota) or a more hardy stock certainly warrants close observation, and Bob Lucas is the man for the job. Later Bob took us down to the point on the St. Johns River where the plant takes in its coolant water supply. I searched all suitable areas nearby and was unable to find Charrua Mussels although Ribbed Mussels were abundant. We could see tankers across the water at Blount Island, and it occurred to us that one of those vessels, not unlikely after a visit to a Venezuelan port, might have provided our city with its first Charrua Mussels, bilge water stowaways from Latin America. Charlotte and I thanked Bob for taking a good two hours of his day off to show us around and patiently educate us on the operation of the plant. We asked for some samples of the Plant's Charruas, and he happily complied. In fact he wished we could take them ALL with us! Epilogue: The mussels disappeared during the winter of 1986 and weren't observed again in northeast Florida until 2006. Reference: Keen, A. M., 1971. Sea shells of tropical west America. Stanford Univ. Press, CA, pp. 1-1064 incl. numerous figs. + 22 pls. |

|