Over the past couple of years, Bill Frank,

noted webmaster and field naturalist, has ventured inland from the

shorelines and expanded his shelling activities and

mollusk-watching, vigorously collecting freshwater and land mollusks

around Duval Co. He has had particular

success with our two species of applesnails and naiads, but his eye

is occasionally distracted by other biota as evidenced by his “In

the forest” webpages, where his photographic

“bycatch” of flowers, insects birds, and herps, is arranged. A

recent addition was Rana

heckscheri Wright,

the River Frog. On first reading the

scientific cognomen, I was struck by two familiar features (in

red) - names which resonate

in the natural and civic heritage of Jacksonville and northeast

Florida.

Firstly I recalled a memoir Jacksonville Shell

Club (JSC) member Clyde Hebert placed in the April, 1974

Shell-O-Gram, the first issue I ever received, as I had begun

practice in Jacksonville that month. Clyde was introduced to conchology by a fellow navy man,

Chief Electricians Mate Leon Mills Wright,

in 1941 while the two were garrisoned in Bermuda. Malacologist Paul

Bartsch (1944), author of Leon's fathers's necrology,

wrote

that Leon was a "steady contributor" to the malacology collections

of the Smithsonian Institution. It must be said that Mr. Wright’s protégé did his mentor

justice as he went forth to make his mark in malacology with his

prowess as a collector, keen wit, and knowledge of the subject as

well as natural history in general, in turn recruiting and enriching

legions of other collectors and observers of mollusks (Lee, 1988).

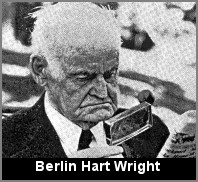

Clyde indicated that his preceptor was the son of Berlin Hart

Wright (1851-1940), a

naturalist-malacologist who worked in Florida and named dozens of

naiads between 1888 and 1934. He published a total of 26 papers in

The Nautilus and left us a fine legacy with his

recognition of a handful of truly new freshwater mussel species

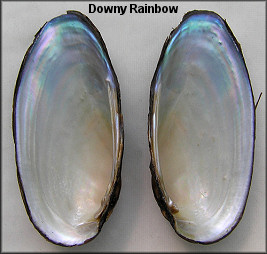

including two in our neighborhood, Elliptio

waltoni (B. H. Wright, 1888) the Florida Lance, and the

Downy Rainbow, which he named Unio

villosus in 1898. Arguably his greatest discovery was a remnant

of the Devonian shark Ctenacanthus wrightii Newberry, 1884

near his home in Yates Co., NY. He also is memorialized in Alasmidonta

wrightiana (Walker, 1901), the Ochlockonee Arcmussel, now

thought to be extinct. Berlin was the son of naturalist Samuel Hart

Wright (1825-1905),

physician, astronomer, botanist and conchologist, who was also a Florida

traveler and namer of mussels. He contributed to the The Nautilus,

which just celebrated its 125th anniversary, in its first year of

existence (B. H. Wright, 1886). In 1888 a genus of asters,

Hartwrightia was named in his honor by the eminent Harvard

botanist Asa Gray (1810-1888). wrote

that Leon was a "steady contributor" to the malacology collections

of the Smithsonian Institution. It must be said that Mr. Wright’s protégé did his mentor

justice as he went forth to make his mark in malacology with his

prowess as a collector, keen wit, and knowledge of the subject as

well as natural history in general, in turn recruiting and enriching

legions of other collectors and observers of mollusks (Lee, 1988).

Clyde indicated that his preceptor was the son of Berlin Hart

Wright (1851-1940), a

naturalist-malacologist who worked in Florida and named dozens of

naiads between 1888 and 1934. He published a total of 26 papers in

The Nautilus and left us a fine legacy with his

recognition of a handful of truly new freshwater mussel species

including two in our neighborhood, Elliptio

waltoni (B. H. Wright, 1888) the Florida Lance, and the

Downy Rainbow, which he named Unio

villosus in 1898. Arguably his greatest discovery was a remnant

of the Devonian shark Ctenacanthus wrightii Newberry, 1884

near his home in Yates Co., NY. He also is memorialized in Alasmidonta

wrightiana (Walker, 1901), the Ochlockonee Arcmussel, now

thought to be extinct. Berlin was the son of naturalist Samuel Hart

Wright (1825-1905),

physician, astronomer, botanist and conchologist, who was also a Florida

traveler and namer of mussels. He contributed to the The Nautilus,

which just celebrated its 125th anniversary, in its first year of

existence (B. H. Wright, 1886). In 1888 a genus of asters,

Hartwrightia was named in his honor by the eminent Harvard

botanist Asa Gray (1810-1888). |

|

Well, it turns out that the

frog-namer was A. H. Wright, and

apparently the herpetologist (the common middle initial

notwithstanding) was

of a different pedigree than the malacological Wright lineage. This

despite the fact that his birthplace was a mere three day’s march

from Penn Yan, home of the Hart Wrights in the Finger Lake country

of upstate New York.

Albert Hazen

Wright (1879-1970) was educated in herpetology near

home, at

Cornell University. It was at Cornell where he met his wife

and lifelong collaborator, Anna Maria Allen. In 1912, 1921, and 1922

they worked in the Okifenokee [his orthography] Swamp and nearby

Callahan, Florida, where the type specimen of the River Frog (now

lost) was collected in "Alligator Swamp." In a footnote to the title

of the description (Wright, 1924) he wrote "The investigation upon

which this article is based was supported by a grant from the

Heckscher Foundation for the Advancement of Research, established at

Cornell University by August Heckscher. The expense of its

publication was borne in part by a second grant from the same

Foundation.” The author went on to remark: “[On] August 18, 1922, we

visited this place at night. Mrs. Wright discovered a queer looking

green frog as she supposed, and, as she was calling to us, we were

startled by a call unlike any Rana we had ever heard.” This

passage is from an entertaining three page chronicle in normal

print, which is followed by an exhaustive description (seven and

one-half pp. of fine print, one table, and two captioned plates with

six and four figures respectively) – an awesome example of detail of

which I can think of no equal in the malacological literature. While

perhaps an extreme example, some of our more laconic molluscan

taxonomists should nota bene.

Dr. Wright spent his

entire career at Cornell and wrote several major herpetological

works, some with the co-authorship of his wife. He also wrote on

historical, including the Sullivan Expedition of 1779 and a history

of his alma mater, and ornithological topics, among them a report on

the bony anatomy of the now-extinct Passenger Pigeon.

All of which brings us to the second familiar name. Wright

introduced the species epithet "heckscheri" to honor his

patron, who, perhaps not due to mere coincidence, had been busying

himself, in lockstep with the Florida real estate boom and less than

twenty miles from frog's type locality alongside "New Dixie Highway"

(Wright, 1924), with the construction of an even newer thoroughfare,

a toll road from Jacksonville to Fort George Island. August

Heckscher (1848-1941),

industrialist, real estate developer, and philanthropist was a

prominent figure in the 20th Century history of New York City and

nearby Huntington, Long Island. Although his name is emblazoned on

the Jacksonville landscape as the toll road became “Heckscher

Drive,” well-known and -traveled by most of Jacksonville’s million

residents, very few of us know much about the man behind the name.

As was JSC founder Gertrude Moller, August

Heckscher was born in Hamburg, Germany. The son of a physician, he

was to become one of the foremost capitalists and philanthropists in

the United States. He attended elementary and high schools in

Germany and Switzerland and then began his business career in 1864

with an importing firm in the town where he was born. Three years

later when his father died, the young Heckscher took his $500

legacy, buckled it inside his belt and started out to seek his

fortune in America.

August Heckscher was to fulfill the American

dream of financial success and personal accomplishment. Arriving in

this country, he went to work in his cousin Richards coal mining

operation as a laborer, while studying English at night. Several

years later he formed a partnership with his cousin under the name

of Richard Heckscher & Company. The firm also concentrated on coal

mining and was eventually sold to the Philadelphia-Reading Railroad.

August Heckscher then expanded his interests into zinc mining and

organized the Zinc and Iron Company, becoming vice-president and

general manager. In 1897, it was consolidated with other zinc and

iron companies into the New Jersey Zinc Company with Heckscher

serving as the general manager. In 1904 he resigned his position

with the New Jersey Zinc Company and organized the Vermont Copper

Company, taking the position of president. He was also to become

president of a number of other iron, coal and power companies.

Heckscher later turned his attentions to the

real estate field, organizing and becoming president of the Anahama

Realty Corporation, which conducted extensive operations in New

York. His keen vision of the opportunities for building expansion

and growth in Manhattan and Long Island led to his reputation as one

of the foremost real estate operators. Some of the early New York

skyscrapers were lauded by the New York Times for the mark

his revolutionary design.

Toward the later years of his life, August

Heckscher began what he later considered the most important chapter of his career, as a

philanthropist. He specialized in social issues and child welfare.

He created the Heckscher Childrens Foundation (now home of El Museo

del Barrio) and sought to eradicate slum dwellings in New York City.

He advocated the erection of model tenement houses to be rented for

as little as $6 a room. Heckscher established playgrounds in lower

Manhattan for children and purchased and dedicated to the public

Heckscher State Park in East Islip, Long Island, a tract of 1,469

acres.

In 1918 Heckscher purchased the Prime property

adjoining the historic Old First Church in Huntington, Long Island,

and, after landscaping it into a park at a total cost of $100,000,

he turned its control over to a board of self-perpetuating trustees.

He also arranged for an Endowment Fund of $70,000 for its upkeep.

Later, an athletic field was added by Heckscher, for school children

and adults. Months later in 1919, August erected a beautiful

beaux-arts fine arts building (now the Heckscher Museum of Art) at a

cost of $100,000. He filled the museum with over 185 works including

art from the Renaissance, the Hudson River School and early

modernist American art. His collection was particularly noteworthy

for including the best American artists of the day such as Ralph

Albert Blakelock, Thomas Eakins, George Inness, and Thomas Moran. In

1920 when the museum opened, the works were valued at many hundreds

of thousands of dollars. Heckscher dedicated this museum and the

park to the people of Huntington, especially the children, with the

following words: “to the little birds that migrate, and to the

little children who fortunately do not.” A year after this gift

August Heckscher gave significant funds for the erection of the

Grand War Memorial on Main Street, to the east of the then

Huntington Library (now known as the Soldiers and Sailors Memorial

Building).

Heckscher and his wife, the former Miss Anna

Atkins of Pottsville, Pennsylvania whom he had married in 1881, were

also known as generous benefactors of the Huntington Hospital and

St. Johns Episcopal Church.

August Heckscher passed away on April 26, 1941 at the age of

92, survived by his two children, Anna and Maurice. The Long

Islander described him in an obituary as perhaps the finest

benefactor that Huntington, NY ever had. In Huntington, Heckscher

was known to many as a warm personal friend. During his years when

Wincoma (a section in north Huntington) was his home, he took a

lively interest in the affairs of the community. August Heckscher

was quoted as saying “God in his great kindness has given me wealth,

which I feel I have neither earned nor deserved. It is my plan to

spend much of this for the uplift of children especially.”

Add to that the honorific of Rana heckscheri Wright,

1924, and a form of immortality may be added to the distinguished

life of August Heckscher.

Acknowledgements: The portrait of August

Heckscher was made available through the kind offices of Mr.

William H. Titus, Registrar & IT

Administrator, and Dr. Kenneth Wayne, Chief Curator, Heckscher

Museum of Art, Huntington, NY.

Dr. M. G. Harasewych, Curator of Malacology, United States

National Museum, Washington DC, provided a copy of the River Frog’s

description (Wright, 1924).

Bartsch, P. , 1944. Berlin Hart Wright

1851-1940. A. M. U. News Bulletin and Annual Report 1943:

11-19 + portrait. Jan.

Hebert, C. H., 1974. Bermuda memories.

Shell-O-Gram 15(3): 4-6. April.

Johnson, C. W., 1906. Samuel Hart Wright.

The Nautilus 19(9): 105-106. Jan.

Lee, H. G., 1988, Clyde Hamilton Hebert.

Shell-O-Gram 29(3): 6. May-June.

Wright, A. H., 1924. A new Bullfrog (Rana

heckscheri) from Georgia and Florida. Proc. Biol. Soc. Wash.

37: 141-152; pl. 11, 12.

Wright, S. H., 1886. New Localities. The

Conchologists’ Exchange 1(6): 27. Dec.

Much of the biographical information was

taken from the Internet:

http://rmc.library.cornell.edu/EAD/htmldocs/RMA01382.html

http://www.wirednewyork.com/forum/archive/index.php/t-3419.html |

wrote

that Leon was a "steady contributor" to the malacology collections

of the Smithsonian Institution. It must be said that Mr. Wright’s protégé did his mentor

justice as he went forth to make his mark in malacology with his

prowess as a collector, keen wit, and knowledge of the subject as

well as natural history in general, in turn recruiting and enriching

legions of other collectors and observers of mollusks (Lee, 1988).

Clyde indicated that his preceptor was the son of Berlin Hart

Wright (1851-1940), a

naturalist-malacologist who worked in Florida and named dozens of

naiads between 1888 and 1934. He published a total of 26 papers in

The Nautilus and left us a fine legacy with his

recognition of a handful of truly new freshwater mussel species

including two in our neighborhood, Elliptio

waltoni (B. H. Wright, 1888) the Florida Lance, and the

Downy Rainbow, which he named Unio

villosus in 1898. Arguably his greatest discovery was a remnant

of the Devonian shark Ctenacanthus wrightii Newberry, 1884

near his home in Yates Co., NY. He also is memorialized in Alasmidonta

wrightiana (Walker, 1901), the Ochlockonee Arcmussel, now

thought to be extinct. Berlin was the son of naturalist Samuel Hart

Wright (1825-1905),

physician, astronomer, botanist and conchologist, who was also a Florida

traveler and namer of mussels. He contributed to the The Nautilus,

which just celebrated its 125th anniversary, in its first year of

existence (B. H. Wright, 1886). In 1888 a genus of asters,

Hartwrightia was named in his honor by the eminent Harvard

botanist Asa Gray (1810-1888).

wrote

that Leon was a "steady contributor" to the malacology collections

of the Smithsonian Institution. It must be said that Mr. Wright’s protégé did his mentor

justice as he went forth to make his mark in malacology with his

prowess as a collector, keen wit, and knowledge of the subject as

well as natural history in general, in turn recruiting and enriching

legions of other collectors and observers of mollusks (Lee, 1988).

Clyde indicated that his preceptor was the son of Berlin Hart

Wright (1851-1940), a

naturalist-malacologist who worked in Florida and named dozens of

naiads between 1888 and 1934. He published a total of 26 papers in

The Nautilus and left us a fine legacy with his

recognition of a handful of truly new freshwater mussel species

including two in our neighborhood, Elliptio

waltoni (B. H. Wright, 1888) the Florida Lance, and the

Downy Rainbow, which he named Unio

villosus in 1898. Arguably his greatest discovery was a remnant

of the Devonian shark Ctenacanthus wrightii Newberry, 1884

near his home in Yates Co., NY. He also is memorialized in Alasmidonta

wrightiana (Walker, 1901), the Ochlockonee Arcmussel, now

thought to be extinct. Berlin was the son of naturalist Samuel Hart

Wright (1825-1905),

physician, astronomer, botanist and conchologist, who was also a Florida

traveler and namer of mussels. He contributed to the The Nautilus,

which just celebrated its 125th anniversary, in its first year of

existence (B. H. Wright, 1886). In 1888 a genus of asters,

Hartwrightia was named in his honor by the eminent Harvard

botanist Asa Gray (1810-1888).![River Frog [Rana heckscheri Wright, 1924]](froggieh.jpg)

![August Heckscher [1848-1941]](hecks.jpg)