Early in November, 2001, impelled by the recent interest expressed in the

pastime of “snail-trapping” on the Internet (specifically on the shellers’

list-serve called “Conch-L”) and at the urging of shutterbug/snailer Bill Frank,

I brought my quarter-century-old “snail-trap” out of retirement. This device is

nothing more than a 4 ft. by 5 ft. by 5/8 in. (formerly; now edited by the

depredations of termites, etc.) plywood. Despite languishing in a shed for

about 20 years, the “trap” produced results in only ten minutes! Bill got about

78 shots of the White Snaggletooth, Depressed Glass, Minute Gem, Florida

Liptooth (top left), and Southern Flatcoil (bottom

left) - all actively crawling on the undersurface when

we flipped over the board.

I live on the bank of a small river, and the water table is

not far below the surface of the back yard. Early that afternoon, as is not

unusual, the lawn was still a little moist with dew, which percolates slowly

into the sodden ground. Things were approximately the same in 1977, when I

routinely placed this board on the grass and examined its underside every

morning or so - after the sprinkler had wet the lawn down at night. No baiting

was involved; any use of beer, etc. was limited to consumption by the

investigator. The program was prosperous indeed - I saw over 100,000 snails and

harvested most of them (to conservation-inclined readers, this is about

1/100,000 the decimation produced by one application of insecticide, which I,

natch, have avoided). Of course most species are tiny - in the case of the

Blade Vertigo, I weighed 446 shells at 0.1273 grams or 0.285 mg. per shell,

which means it would take about a billion to match the world record Tridacna

gigas in mass). The following are the species (in "systematic order" and

with links to images) I found: I live on the bank of a small river, and the water table is

not far below the surface of the back yard. Early that afternoon, as is not

unusual, the lawn was still a little moist with dew, which percolates slowly

into the sodden ground. Things were approximately the same in 1977, when I

routinely placed this board on the grass and examined its underside every

morning or so - after the sprinkler had wet the lawn down at night. No baiting

was involved; any use of beer, etc. was limited to consumption by the

investigator. The program was prosperous indeed - I saw over 100,000 snails and

harvested most of them (to conservation-inclined readers, this is about

1/100,000 the decimation produced by one application of insecticide, which I,

natch, have avoided). Of course most species are tiny - in the case of the

Blade Vertigo, I weighed 446 shells at 0.1273 grams or 0.285 mg. per shell,

which means it would take about a billion to match the world record Tridacna

gigas in mass). The following are the species (in "systematic order" and

with links to images) I found:

-

Leidyula floridana (Leidy, 1851)

Florida Leatherleaf

- Gastrocopta pentodon

(Say, 1822) Comb Snaggletooth

- Gastrocopta rupicola

(Say, 1821) Tapered Snaggletooth

-

Gastrocopta tappaniana (C. B.

Adams, 1841) White Snaggletooth

-

Pupisoma dioscoricola (C. B. Adams,

1845) Yam Babybody

-

Vertigo milium (Gould, 1840) Blade

Vertigo

-

Vertigo ovata Say, 1822 Ovate

Vertigo

-

Vertigo rugosula Sterki, 1890,

Striate Vertigo

- Strobilops aeneus

Pilsbry, 1926 Bronze Pinecone

- Strobilops texasianus

Pilsbry and Ferriss, 1906 Southern Pinecone

-

Succinea unicolor Tryon, 1866

Squatty Ambersnail

- Philomycus

carolinianus (Bosc, 1802) Carolina Mantleslug

- Helicodiscus parallelus

(Say, 1821) Compound Coil

- Deroceras laeve (Müller,

1774) Meadow Slug

- Glyphyalinia solida

(H. B. Baker, 1930) Imperforate Glyph*

- Glyphyalinia umbilicata

(Singley in Cockerell, 1893) Texas Glyph

- Hawaiia

minuscula (A. Binney, 1841) Minute Gem

- Nesovitrea dalliana

(Pilsbry and Simpson, 1888) Depressed Glass

- Zonitoides arboreus

(Say, 1817) Quick Gloss

- Dryachloa dauca

Thompson and Lee, 1981 Carrot Glass

- Euconulus trochulus

(Reinhart, 1885) Silk Hive

-

Euglandina rosea (Férussac, 1821)

Rosy Wolfsnail

Species Discussion

-

Daedalochila avara(Say, 1818)

Florida Liptooth

-

Polygyra cereolus

(Mühlfeld, 1816)

Southern Flatcoil

- Polygyra

septemvolva

Say, 1818 Florida Flatcoil

-

Allopeas gracile

(Hutton, 1834)

Graceful Awlsnail

-

Opeas pyrgula

Schmacker and Boettger,

1891 Sharp Awlsnail

That's 27 species, nearly 40% known from our region of Florida (see

Northeast Florida Terrestrial Mollusk Checklist),

many by the hundreds of individuals, some by the tens of thousands. With this

kind of return, you're bound to learn things. Two species, a Striate Vertigo

and a Florida Liptooth,

were represented by hundreds of

specimens including a single perfect sinistral individual of each. Some readers might have note the anachronistic "1981" in the

litany above. That's because Dryachloa dauca Thompson and Lee, 1981, the

Carrot Glass, wasn't named until after the 1977 snail trapping campaign. In

fact, the species was described based on "trapped" specimens, and the plywood

is/was arguably the type locality!

That's 27 species, nearly 40% known from our region of Florida (see

Northeast Florida Terrestrial Mollusk Checklist),

many by the hundreds of individuals, some by the tens of thousands. With this

kind of return, you're bound to learn things. Two species, a Striate Vertigo

and a Florida Liptooth,

were represented by hundreds of

specimens including a single perfect sinistral individual of each. Some readers might have note the anachronistic "1981" in the

litany above. That's because Dryachloa dauca Thompson and Lee, 1981, the

Carrot Glass, wasn't named until after the 1977 snail trapping campaign. In

fact, the species was described based on "trapped" specimens, and the plywood

is/was arguably the type locality!

A few weeks later, on Thanksgiving Day, while attempting to busy myself with

yard work (in forced exile from my wife's kitchen), I noticed a line of drifted

wrack along the riverbank in back of my house - just a few feet from where the

snail-trapping device had been deployed earlier. Following instincts shared by

many of us, I harvested the stuff (about a pint), sifted it, and spread it out

under the microscope. Shortly before sitting down for the annual feast, I had

extracted the following empty shells from among the Styrofoam nuggets, insect

parts, stems, seeds, and other plant debris:

| Gastrocopta rupicola

(Say, 1821) Tapered Snaggletooth (7 shells) |

| Gastrocopta tappaniana

(C. B. Adams, 1842) White Snaggletooth (5 shells) |

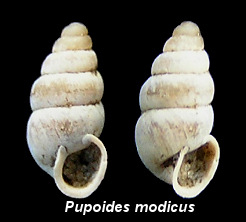

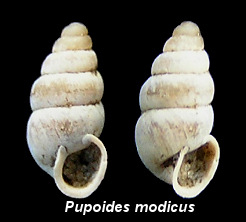

| Pupoides modicus

(Gould, 1848) Island Dagger (1 shell) |

| Vertigo ovata Say,

1822 Ovate Vertigo (7 shells) |

|

Vertigo oralis

Sterki, 1898 Palmetto Vertigo (2 shells) |

| Strobilops texasianus

Pilsbry and Ferriss, 1906 Southern Pinecone (1 shell) |

| Succinea unicolor

Tryon, 1866 Squatty Ambersnail (2 shells) |

| Hawaiia minuscula (Binney,

1841) Minute Gem (1 shell) |

| Nesovitrea dalliana (Pilsbry

and Simpson, 1888) Depressed Glass (1 shell) |

|

Ventridens demissus

(A. Binney, 1843) Perforate Dome (2 shells) |

| Polygyra cereolus (Mühlfeld,

1816) Southern Flatcoil (29 shells) |

| Allopeas gracile

(Hutton, 1834) Graceful Awlsnail (1 shell) |

|

Huttonella bicolor

(Hutton, 1834) Two-tone Gullela (1 shell) |

| |

| plus the one shell of each

of these two aquatic species: |

| Rangia

cuneata (G. B. Sowerby I, 1831) Atlantic Rangia |

| Mytilopsis leucophaeata

(Conrad, 1831) Dark Falsemussel |

I have indented the names of 4 of the total 13 landsnail species because they

not only were they never found among the 27 species/100,000 individuals (list

above) found clinging to my snail trap, they had never before been found in my

yard at all. What a surprise!

But maybe

not so shocking. Landsnails can live very close to freshwater, but when swept

into such watercourses are often doomed to perish by drowning. Both living and

dead landsnails tend to float, and the abundance of this material in freshwater

"drift" is legendary among collectors (see

Dream Stream Stems Teem With Stenotremes). Thus I cashed in on a method to expand the diversity of my yard collections.

Here are some factors relating to my catching the "new" species:

(1) Pupoides modicus

likes disturbed, dry habitats not found in my yard. There is, however, a

railroad cut (right down to the river) just a few hundred yards from my place,

and I've found this species very close to the river along the railroad tracks.

(2) Vertigo oralis is

a "swamp beast," occurring on palmettos and in very damp leaf litter in

swamplands typically along rivers around here. That habitat is not present in

my yard but is visible a few hundred yards away.

(3) Ventridens demissus is a special critter. I and a few other collectors have witnessed this

native species actually extending its range through northeast Florida over the

last quarter century. It reached Duval Co. in the last decade (about the same

time as the Eurasian Turtle Dove), and it has a penchant for disturbed habitat

(like P. modicus). It may be in the process of colonizing my back yard

by rafting in.

(4) Huttonella bicolor

is a non-indigenous species (like Allopeas gracile above); the dynamics

of its appearance are likely similar to V. demissus.

As I reflect on my good fortune, I see a moral for collectors located almost

anywhere in the world, of almost any age and level of experience:

(1) You can enjoy collecting with thrift and

simplicity.

(2) There will always be something "new under the sun."

(3) The wisdom of the Yogi Berra-style aphorism "shells are where you find

them," is again demonstrated.

|

I live on the bank of a small river, and the water table is

not far below the surface of the back yard. Early that afternoon, as is not

unusual, the lawn was still a little moist with dew, which percolates slowly

into the sodden ground. Things were approximately the same in 1977, when I

routinely placed this board on the grass and examined its underside every

morning or so - after the sprinkler had wet the lawn down at night. No baiting

was involved; any use of beer, etc. was limited to consumption by the

investigator. The program was prosperous indeed - I saw over 100,000 snails and

harvested most of them (to conservation-inclined readers, this is about

1/100,000 the decimation produced by one application of insecticide, which I,

natch, have avoided). Of course most species are tiny - in the case of the

Blade Vertigo, I weighed 446 shells at 0.1273 grams or 0.285 mg. per shell,

which means it would take about a billion to match the world record Tridacna

gigas in mass). The following are the species (in "systematic order" and

with links to images) I found:

I live on the bank of a small river, and the water table is

not far below the surface of the back yard. Early that afternoon, as is not

unusual, the lawn was still a little moist with dew, which percolates slowly

into the sodden ground. Things were approximately the same in 1977, when I

routinely placed this board on the grass and examined its underside every

morning or so - after the sprinkler had wet the lawn down at night. No baiting

was involved; any use of beer, etc. was limited to consumption by the

investigator. The program was prosperous indeed - I saw over 100,000 snails and

harvested most of them (to conservation-inclined readers, this is about

1/100,000 the decimation produced by one application of insecticide, which I,

natch, have avoided). Of course most species are tiny - in the case of the

Blade Vertigo, I weighed 446 shells at 0.1273 grams or 0.285 mg. per shell,

which means it would take about a billion to match the world record Tridacna

gigas in mass). The following are the species (in "systematic order" and

with links to images) I found: That's 27 species, nearly 40% known from our region of Florida (see

That's 27 species, nearly 40% known from our region of Florida (see