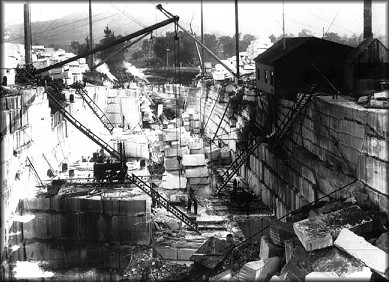

| These

quarries began as America's first commercial marble industry. Mining was

begun in neighboring South Dorset by Isaac Underhill in 1785 and

flourished for some 130 years. Dorset marble, as this deposit came to be

called, built the largest marble structure in the U.S., the New York

Public Library, as well as the library of Brown University and Memorial

Continental Hall of the Daughters of the American Revolution in

Washington, D.C. It was also used for over 5000 headstones over the

fallen soldiers at the battle of Gettysburg.

I recalled that the principal stuff of marble, calcium

carbonate, is the mineral terrestrial snails (just as marine and aquatic ones)

use to fashion their shells; consequently these mollusks tend to prosper in

habitats on or very near exposures of this rock. Furthermore, after the demise

of their inhabitants, the empty shells persist in situ far longer due to

the buffering of acidic groundwater that etches and ultimately dissolves their

mineral content. Thus collecting is easy and usually profitable. With geographic

guidance from brother-in-law, Hamilton "Ham" Hadden III, and the company

of Ed Cavin

(Jacksonville, FL), I set out by car to approach the point on the mountainside

we had observed from the patio of the Homestead. This being a well-contrived

collecting trip, our expectations were high. Yet, as we all know, too much

scheming can be a recipe for failure, so our prospects were tempered with various

practicalities such as our fitness for the ultimate assault of the mountain by

foot. First a word about American landsnails, and those of Vermont

in particular. It is apparent that the state has never been a popular

destination for snail-collectors, and very little has appeared in the literature

about its molluscan fauna. Most references are in the form of simple

locality-citations in a variety of works with a far wider geographic scope or in

phylogenetically-restricted studies. In the nineteenth century Charles Baker

Adams (1814-1853)* wrote a few short papers on the state's fauna during his

tenure at Middlebury College (1838-1848) including the years he was the head of

the Vermont Geological Survey (1845-1848). Monographic treatments of the

non-marine mollusca of the other New England states have appeared in the

literature over the last century and a half, but nothing of that scope has been

dedicated to the malacofauna of Vermont.

As a student at Williams College, just over the Massachusetts

line, an hour to the south, I wrote my senior honors thesis (unpublished)

entitled The biology of the testaceous Mollusca of the Williamstown area.

It included reports of three 1961 collecting expeditions to the vicinity of

Pownal, a Vermont town several miles south of Manchester but also in Bennington

Co. One of these three stations was an abandoned marble quarry! A total of 25

species was collected, and we will see below how this assemblage relates to the

efforts in the neighborhood of the Homestead.

In 1985 Leslie Hubricht, an inveterate student of our

country's non-marine mollusks and one-time visitor to the Lee domicile,

published a zoogeographical study The distribution of the native land

mollusks of the Eastern United States. Using literature records, his

personal collections (43,000 lots), and critically-reviewed material in the

leading American museums, he produced appropriately-edited maps showing every

county inhabited (or not) by each of the 523 total species. As expected,

Vermont was not prominently-represented in this work. He demonstrated 49

species from the state, and virtually all of these were found in less than half

the state's counties. Of the 14 counties in Vermont, Bennington was the most

often-represented - with 27 species (based principally on my 25, which I had

communicated to him in the 1970's), of which 15 were found nowhere else in the

state. Second place went to Windsor Co., just to the northeast of Bennington

Co., with 20 species (four unique to the state), and third was Orleans Co., on

the Canadian border, with 12 species (three unique).

Getting back to the Mt. Aeolus marble quarry expedition....

After being escorted by "Ham" to the trailhead, we debarked afoot and made a 45

minute ascent of the mountain with moderate effort. After passing through a

forest of hemlock, birch, beech, and maple on an unusually straight and

commodious trail, we came in sight of the areas of exposed marble, and I paused

to reflect on what I knew of this formation. It started as limey mud formed by

long extinct invertebrates as they died and sank to the bottom of a shallow

Cambrian sea about 463,000,000 years ago. Later, additional sediments and

collisions between continental plates applied pressure and heat to these limey

strata - metamorphosing limestone to marble. Here we were at the end of our

ascent, and Ed and I immediately noticed empty snail shells for the first time

on the trek. After about a half-hour of our visual reconnaissance and

hand-picking of about five dozen shells

(figure 1) of about ten species, I scooped up several handfuls of the humus

in the rock crevices and stashed them in a one quart ziplock bag. This stuff

was later dried, sifted, and sorted under the microscope and, mirabile dictu,

nearly a hundred more shells were culled. The total species count was a

fairly astounding 23. The list follows (phylogenetic order; scientific name,

author, date of description, official vernacular name;** typeface in

green indicates a

new county record; new state records are indented): Getting back to the Mt. Aeolus marble quarry expedition....

After being escorted by "Ham" to the trailhead, we debarked afoot and made a 45

minute ascent of the mountain with moderate effort. After passing through a

forest of hemlock, birch, beech, and maple on an unusually straight and

commodious trail, we came in sight of the areas of exposed marble, and I paused

to reflect on what I knew of this formation. It started as limey mud formed by

long extinct invertebrates as they died and sank to the bottom of a shallow

Cambrian sea about 463,000,000 years ago. Later, additional sediments and

collisions between continental plates applied pressure and heat to these limey

strata - metamorphosing limestone to marble. Here we were at the end of our

ascent, and Ed and I immediately noticed empty snail shells for the first time

on the trek. After about a half-hour of our visual reconnaissance and

hand-picking of about five dozen shells

(figure 1) of about ten species, I scooped up several handfuls of the humus

in the rock crevices and stashed them in a one quart ziplock bag. This stuff

was later dried, sifted, and sorted under the microscope and, mirabile dictu,

nearly a hundred more shells were culled. The total species count was a

fairly astounding 23. The list follows (phylogenetic order; scientific name,

author, date of description, official vernacular name;** typeface in

green indicates a

new county record; new state records are indented): |

Getting back to the Mt. Aeolus marble quarry expedition....

After being escorted by "Ham" to the trailhead, we debarked afoot and made a 45

minute ascent of the mountain with moderate effort. After passing through a

forest of hemlock, birch, beech, and maple on an unusually straight and

commodious trail, we came in sight of the areas of exposed marble, and I paused

to reflect on what I knew of this formation. It started as limey mud formed by

long extinct invertebrates as they died and sank to the bottom of a shallow

Cambrian sea about 463,000,000 years ago. Later, additional sediments and

collisions between continental plates applied pressure and heat to these limey

strata - metamorphosing limestone to marble. Here we were at the end of our

ascent, and Ed and I immediately noticed empty snail shells for the first time

on the trek. After about a half-hour of our visual reconnaissance and

hand-picking of about five dozen shells

(figure 1) of about ten species, I scooped up several handfuls of the humus

in the rock crevices and stashed them in a one quart ziplock bag. This stuff

was later dried, sifted, and sorted under the microscope and, mirabile dictu,

nearly a hundred more shells were culled. The total species count was a

fairly astounding 23. The list follows (phylogenetic order; scientific name,

author, date of description, official vernacular name;** typeface in

green indicates a

new county record; new state records are indented):

Getting back to the Mt. Aeolus marble quarry expedition....

After being escorted by "Ham" to the trailhead, we debarked afoot and made a 45

minute ascent of the mountain with moderate effort. After passing through a

forest of hemlock, birch, beech, and maple on an unusually straight and

commodious trail, we came in sight of the areas of exposed marble, and I paused

to reflect on what I knew of this formation. It started as limey mud formed by

long extinct invertebrates as they died and sank to the bottom of a shallow

Cambrian sea about 463,000,000 years ago. Later, additional sediments and

collisions between continental plates applied pressure and heat to these limey

strata - metamorphosing limestone to marble. Here we were at the end of our

ascent, and Ed and I immediately noticed empty snail shells for the first time

on the trek. After about a half-hour of our visual reconnaissance and

hand-picking of about five dozen shells

(figure 1) of about ten species, I scooped up several handfuls of the humus

in the rock crevices and stashed them in a one quart ziplock bag. This stuff

was later dried, sifted, and sorted under the microscope and, mirabile dictu,

nearly a hundred more shells were culled. The total species count was a

fairly astounding 23. The list follows (phylogenetic order; scientific name,

author, date of description, official vernacular name;** typeface in

green indicates a

new county record; new state records are indented):