|

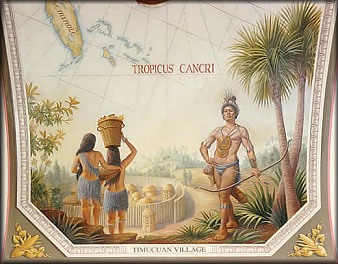

History Of The Talbot Islands - 6,000 Years Of Human Habitation* What visitors enjoy today at the Talbot Islands parks is the product of over six thousand years of human activity, and tens of thousands of years of natural forces. The only static aspect of the parks is the dynamic nature of the islands. When humans first reached the Florida peninsula approximately twelve thousand years ago, they encountered an environment much different from our own. The climate was much drier and cooler, resulting in few lakes and streams. Because this was the last Ice Age, much of the world's water was frozen in the large ice glaciers covering much of North America. For North Florida, this meant a coastline eighty to a hundred miles further out than the present shore. The fauna was also much different from today, and included now extinct animals such as mammoths, horses, giant sloths, and saber-toothed tigers. In 4,000 BC, when the earliest evidence for human occupation of the Talbot Islands can be dated to occur, the climate had become much as it is today. These early peoples, known to scholars as Archaic people, began to adapt to the marine environment. Slowly, that developed a way of life we call today the St. Johns Culture. Signs of this long lasting culture include the extensive shell mounds on Fort George and Big Talbot islands, and the presence of the Western hemisphere's earliest pottery. The St. Johns Culture was still practiced when the Europeans arrived in the 1500s. The Europeans began to call these people the Timucua.

The first known Europeans to arrive on the Talbot Islands were the French, in 1562. They first landed on Fort George Island - erecting a monument to commemorate the event - before exploring other areas in the Southeast. Two years later, the French returned to this area to construct Fort Caroline on the St. Johns Bluffs, and to trade with the native peoples—including the peoples of the Talbot Islands. The following year, 1565, the Spanish arrived to found St. Augustine, and expelled the French in the process. Over the next two centuries, the Spanish settled Florida. One of their goals was to Christianize the native peoples. This was attempted through a series of Catholic missions. One of the largest missions was San Juan del Puerto, located on the east side of Fort George Island. It is from this mission that the St. Johns River gets its name. Smaller missions were located on Big Talbot and Amelia islands. By the late 1700s, all of Florida's original inhabitants had died off from disease and warfare. Starting during the brief British period (1763-83), and continuing through the Second Spanish period (1783-1821), the Talbot Islands were used for plantation agriculture. Oranges, sugar, indigo, and cotton were grown. Little Talbot Island was used for horse and cattle grazing. This plantation culture continued after the United States took possession of Florida in 1821. Prominent planters of this period included Spicer Christopher, John Houston, John McQueen, and Zephaniah Kingsley. Plantations continued to thrive until the late 1800s, when tourism took over. At least three hotels were in operation on Fort George Island during this period. Since there were no roads, patrons—who were the elite of their day - were brought in by steamboat. In the 1920s, A1A was built connecting the islands with the mainland, enabling the common locals to enjoy fishing and swimming at the islands. In 1952, the state opened Little Talbot Island State Park. By the 1960s, Kingsley Plantation was also being run by the state here on Fort George Island. With the 1980s came several changes. They began in 1984, when Big Talbot Island, to the northwest of Little Talbot Island, was opened as a State Park. This was soon followed by 300 acres of the south tip of Amelia Island becoming a State Recreation Area. In the late 1980s, the National Park Service began managing Kingsley Plantation. It was not until after a failed attempt at building a resort, that some properties sold on Fort George were united to form Fort George Island State Cultural Site. Today, the Talbot Islands attract visitors to the unique cultural and natural heritage found here. This heritage stretches back over six thousand years – and with visitors such as yourself, it will continue well into the future to come. *Information courtesy of Bob Joseph, Talbot Island Parks Manager. |

Several modem myths surround the Timucua. They did not stand over seven

feet tall, they were not the ancestors of the modem Seminoles, they were

not cannibals, and they did not drink a tea that made them vomit (although

they did perform rituals that involved vomiting). No one knows what they

called themselves, since the term "Timucuan" was derived from a name

originally recorded by the French, that the native peoples in our area

gave to an inland group around present day Orange Park Florida.

Several modem myths surround the Timucua. They did not stand over seven

feet tall, they were not the ancestors of the modem Seminoles, they were

not cannibals, and they did not drink a tea that made them vomit (although

they did perform rituals that involved vomiting). No one knows what they

called themselves, since the term "Timucuan" was derived from a name

originally recorded by the French, that the native peoples in our area

gave to an inland group around present day Orange Park Florida.