|

Which Way Does A Sundial Turn? By Harry G. Lee |

|||

|

|

|||

|

Recently the author received two anomalous

specimens of a common and widespread member of the Sundial Shell

family (aptly dubbed Solariidae, now Architectonicidae) from two

adroit dealers, Phillip Clover and Guido Poppe. Each specimen was

said to be "sinistral," yet there were a few unusual features that

came to light after closer examination. |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

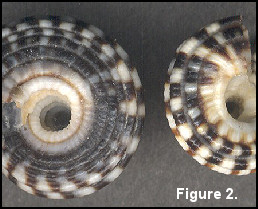

| In the images of paired shells (figures 2-6), the normal specimen is

on the left. Figure 2. Adapical (umbilical) aspect of the body whorl is juxtaposed with that of the abnormal shell from Negros. Figure 3. Same aspect of the normal shell next to the apical aspect of the abnormal. Figure 4. Apical aspect of both shells. Figure 5. Apical aspect of the normal with adapical of the abnormal. Accounting for some aberration of the contour of the abnormal shell, it is apparent that the sculpture of the adapical (basal) aspect of the normal shell, with more, smaller, and more finely-beaded cords, is far more similar to that of the apical aspect of the abnormal one (figure 2,3). Likewise, the less numerous, larger, more coarsely-beaded sculpture basal (adapical) cords of the apical half of the normal shell's body whorl more closely resemble that of the basal aspect of the abnormal (figure 4,5).  Now let's look more closely at the aperture (figure 6), which in

this species has two distinct grooves on the columellar aspect as

visible on the normal specimen. Note one groove (as well as the

ornate cord runs back from it around the umbilical rim) is at the

anterior (adapical) aspect of the columella. In the abnormal shell

that groove is at the apical ("opposite") aspect of the columella,

where the aperture joins the body whorl (and the ornate cord is

hidden beneath the latter).

Now let's look more closely at the aperture (figure 6), which in

this species has two distinct grooves on the columellar aspect as

visible on the normal specimen. Note one groove (as well as the

ornate cord runs back from it around the umbilical rim) is at the

anterior (adapical) aspect of the columella. In the abnormal shell

that groove is at the apical ("opposite") aspect of the columella,

where the aperture joins the body whorl (and the ornate cord is

hidden beneath the latter). It may help to think of this anomalous shell by an imaginary process

of transformation. Think of inserting the finger of a tiny rubber

glove through the umbilicus at the aperture and pushing it all the

way to the other end along this central axis. Now imagine the shell

becoming the same consistency as, and attached to, the glove finger.

Now slowly pull the fingertip through the finger so as to turn it

inside out. The spire will gradually shorten and then emerge through

the umbilicus. After a little more eversion, the transmuted shell

becomes apparently right-coiling and, furthermore, the apertural

grooves and outer shell sculpture are just (well almost) like that

of the normal shell. The latter features would not be in normal

position if the anomalous shell were a truly (orthostrophic)

sinistral specimen and put through this same contortion; they'd be

opposite. Ergo: the anomalous shell in figures 2 through 6 is "hyperstrophic

pseudosinistral" - also dubbed "ultradextral," very much like the

larval shell discussed above. Without doing the rubber glove trick,

we can correct the anomalous position of the apertural groove by

turning the aberrant shell "upside down" (as the shell on the right

of figure 1); figure 7 shows the "upside down" aperture of the anomalous

shell (bottom image) to have the groove on the same (lower; in the

photo) end of the columella as the normal specimen. Corollary to

this analysis: Hyperstrophic and orthostrophic shells of a single

species are not mirror images of one another - even if they exhibit

the same dimensions whereas true (orthostrophic) sinistral and

dextral forms of a single species will match up in a mirror; on them

the rubber glove technique fails.

It may help to think of this anomalous shell by an imaginary process

of transformation. Think of inserting the finger of a tiny rubber

glove through the umbilicus at the aperture and pushing it all the

way to the other end along this central axis. Now imagine the shell

becoming the same consistency as, and attached to, the glove finger.

Now slowly pull the fingertip through the finger so as to turn it

inside out. The spire will gradually shorten and then emerge through

the umbilicus. After a little more eversion, the transmuted shell

becomes apparently right-coiling and, furthermore, the apertural

grooves and outer shell sculpture are just (well almost) like that

of the normal shell. The latter features would not be in normal

position if the anomalous shell were a truly (orthostrophic)

sinistral specimen and put through this same contortion; they'd be

opposite. Ergo: the anomalous shell in figures 2 through 6 is "hyperstrophic

pseudosinistral" - also dubbed "ultradextral," very much like the

larval shell discussed above. Without doing the rubber glove trick,

we can correct the anomalous position of the apertural groove by

turning the aberrant shell "upside down" (as the shell on the right

of figure 1); figure 7 shows the "upside down" aperture of the anomalous

shell (bottom image) to have the groove on the same (lower; in the

photo) end of the columella as the normal specimen. Corollary to

this analysis: Hyperstrophic and orthostrophic shells of a single

species are not mirror images of one another - even if they exhibit

the same dimensions whereas true (orthostrophic) sinistral and

dextral forms of a single species will match up in a mirror; on them

the rubber glove technique fails. In case you're wondering, all the shell features discussed were also exhibited by the other anomalous specimen (on the right of figure 1), making it also hyperstrophic pseudosinistral rather than truly (orthostrophic) sinistral. Furthermore, three congeners, Heliacus implexus (Michel, 1845) [Ekawa, 1991 as H. dorsuosus (Hinds, 1844, a nude name teste Bieler, 1993], H. bicanaliculatus (Valenciennes, 1832) [Lagoda, 1868 as H. variegatus, a misidentification which was perpetuated for over a century teste Robertson and Merrill, 1963], and H. cylindricus (Gmelin, 1791) [Robertson and Merrill, 1963] have been reported to exhibit the same pseudosinistral condition. Like our shells, each of these is unnaturally elongate. Robertson and Merrill (1963) demonstrated compelling evidence for hyperstrophy including the operculum morphology with that of the shell. Robertson (1974) went on record stating that "(true) sinistrality (is) unknown in the Architectonicidae," confirming this later (Robertson, 1993). So it appears that, throughout life, thus far all Sundials, like the dials on the non-digital chronometer descendants of their namesake, turn clockwise. This condition is has come to be the equivalent of right-handedness, which various cultures have deemed more virtuous and functional (linguistics reminds us: "dexterous" and "adroit" like Clover and Poppe above) than left-handedness ("sinister"). Perhaps aptly, the dextral condition also predominates in the gastropod world, and, at present, Sundials cannot claim exemption from majority rule. A shell of the South African Turbo sarmaticus Linnaeus, 1758 with a the same kind of anomaly is featured at http://www.jaxshells.org/tursar.htm Bieler, R., 1993. Architectonicidae of the Indo-Pacific (Mollusca: Gastropoda). G. Fisher, Stuttgart, pp. 1-377 incl. 286 figs., 3 pls. Ekawa, K., 1991. A "sinistral" abnormality of Heliacus dorsuosus (Hinds). The Chiribotan 21(4): 87-88 April 3. Lagoda, A. de, 1868 Note sur une variété abnormale de Torinia variegata, Lamarck. Journal de Conchyliologie 16: 264-265; pl. 9, fig. Robertson, R., 1974. Sinistrality unknown in the Architectonicidae. La Conchiglia 6(60): 14 Feb. Robertson, R., 1993. Snail handedness. The coiling direction of gastropods. National Geographic Research and Exploration 9(1): Robertson, R. and A. S. Merrill, 1963. Abnormal dextral hyperstrophy in post-larval Heliacus (Gastropoda: Architectonicidae). The Veliger 6: 76-79 Oct. 1. |

|||