|

On April 6,

2007 Ed Cavin and I (Harry Lee) set out to find an authentic specimen of the

type species of Daedalochila. We had a very specific quarry

in the cross-hairs - the snail that America's first native-born

conchologist named Polygyra auriculata, the Ocala Liptooth.

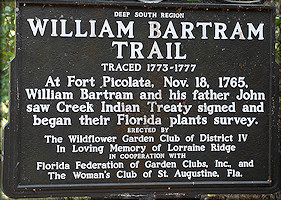

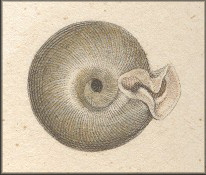

Say (1818: 276) wrote: "This curious species we found near St.

Augustine, East Florida, in a moist situation. They were observed in

considerable numbers ..." Say never illustrated his snail, but an

early engraving (Binney,

1857: pl. 47, fig. 1 - see image, left) was consulted. The text and figure gave us a bit of reassurance for the

feasibility of our mission, but, after nearly 200 years, we expected

to encounter a considerable loss of suitable habitat and other

environmental degradation. The expedition certainly wasn't a

pre-ordained slam-dunk. To improve our chances of success, a closer

look at the history of Say's discovery was in order. On April 6,

2007 Ed Cavin and I (Harry Lee) set out to find an authentic specimen of the

type species of Daedalochila. We had a very specific quarry

in the cross-hairs - the snail that America's first native-born

conchologist named Polygyra auriculata, the Ocala Liptooth.

Say (1818: 276) wrote: "This curious species we found near St.

Augustine, East Florida, in a moist situation. They were observed in

considerable numbers ..." Say never illustrated his snail, but an

early engraving (Binney,

1857: pl. 47, fig. 1 - see image, left) was consulted. The text and figure gave us a bit of reassurance for the

feasibility of our mission, but, after nearly 200 years, we expected

to encounter a considerable loss of suitable habitat and other

environmental degradation. The expedition certainly wasn't a

pre-ordained slam-dunk. To improve our chances of success, a closer

look at the history of Say's discovery was in order.

In the autumn of 1817 Say set sail from Philadelphia, where,

at age 40 he was one of the members of the nascent Academy of

Natural Sciences (ANSP), only in its fifth year of existence. In the

company of naturalists William Maclure, George Ord, and Titian R.

Peale he made his way to Charleston and Savannah, where the group

chartered a 30 ton sloop, which eventually took them into the St.

Johns River (Lee, 1976). On Jan. 30, 1818, Say wrote from St.

Mary's, Georgia: "... we shall be off in about three or four days

for the promised land, a portion of which is now in sight. Our plan

is to ascend as far as convenient the River St. Johns, pursuing

pretty much the track of Bartram, my excellent and ingenious

relative" (Weiss and Ziegler, 1931: 55-56). [Pioneer Florida

naturalist William Bartram was Say's great uncle and William's

father, John, was his enate great grandfather.] Later Say

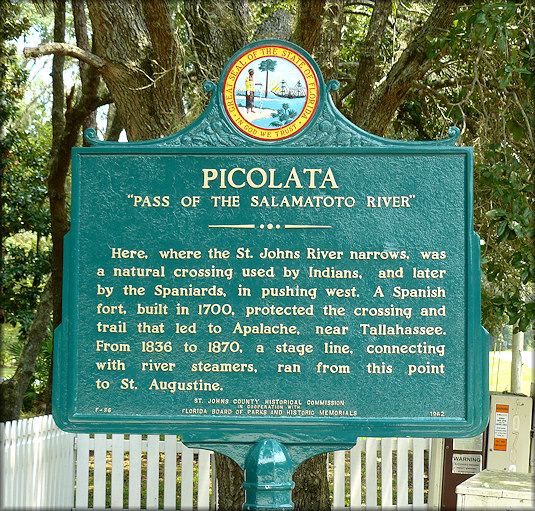

wrote "This noble river we ascended as far a Picolata, an old

Spanish fortress now in ruins, about 100 miles [a considerable, but

unintentional exaggeration] from its mouth ... From Picolata we

crossed the country on foot to St. Augustine" (Weiss and Ziegler,

1931: 58; also see the plaque shown below, which includes a

tribute to late Jacksonville Shell Club veteran member Lorraine

Ridge).

That was probably in late Feb. or March, 1818. Fast Forward

to April, 2007 and look, as we did, at another historical plaque

(illustrated below) positioned at the SE corner of the intersection of SR 13

(The Bartram Trail, blazed by Say's excellent and ingenious

relative) and the western terminus of CR 208. Judging from Say's

narrative and the plaque's indication, it seems a near certainty

that the latter highway follows the course of the carriage road

taken by Thomas Say and his co-expeditioners from Picolata to St.

Augustine. We drove all twenty miles of CR 208 to the heart of the

nation's oldest city. The road passes through potato fields, other

agricultural land, pine flatwoods, low deciduous forest, and

swampland. The last few miles are heavily developed, with commercial

and residential real estate dominating the landscape.

Our collecting strategy was to respectfully place ourselves

in the shoes of Say, Maclure, Ord, and Peale. "Near St. Augustine" is

a bit imprecise, but it indicates that the snail was not taken in

the city that the expeditioners knew. That left

the stretch of 208

from the Old City to Picolata. Accordingly we stopped the car at

fairly regular intervals along CR 208, debarking at whenever "a

moist situation" which seemed to have promise was seen. In the

course of three hours no less than ten stations were made. At one

station some dead shells were found (along with a well-nourished

Pygmy Rattlesnake), but none of the other stops produced any

specimens (of D. auriculata that is; a Water Moccasin was

encountered, however). In near exasperation, we returned to the one

productive spot and, after nearly an hour of searching - without

re-encountering the rattlesnake - a living specimen of the Ocala

Liptooth was found in the grassy swale bank along the road.

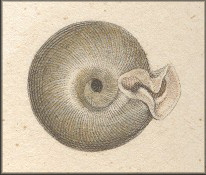

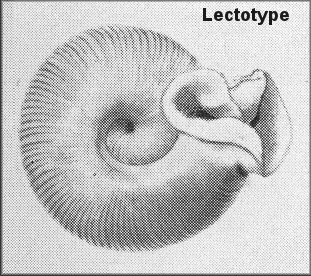

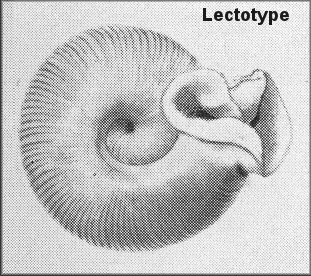

Measuring a little over a half-inch, this snail is included, along

with a dozen empty shells of its species, in the accompanying

montage of illustrations. We believe these shells qualify as

topotypes (specimens collected in the same place of the type lot), which

imparts a certain authenticity to their identity. Furthermore, they

are dead ringers for the lectotype, which Say brought back to

Philadelphia in the Spring of 1818 (ANSP

57066a; plate 4; Pilsbry, 1940: fig. 384-1 - see image, above, left). Also see:

Compendium of

Daedalochila type material - a pictorial gallery (page one) the stretch of 208

from the Old City to Picolata. Accordingly we stopped the car at

fairly regular intervals along CR 208, debarking at whenever "a

moist situation" which seemed to have promise was seen. In the

course of three hours no less than ten stations were made. At one

station some dead shells were found (along with a well-nourished

Pygmy Rattlesnake), but none of the other stops produced any

specimens (of D. auriculata that is; a Water Moccasin was

encountered, however). In near exasperation, we returned to the one

productive spot and, after nearly an hour of searching - without

re-encountering the rattlesnake - a living specimen of the Ocala

Liptooth was found in the grassy swale bank along the road.

Measuring a little over a half-inch, this snail is included, along

with a dozen empty shells of its species, in the accompanying

montage of illustrations. We believe these shells qualify as

topotypes (specimens collected in the same place of the type lot), which

imparts a certain authenticity to their identity. Furthermore, they

are dead ringers for the lectotype, which Say brought back to

Philadelphia in the Spring of 1818 (ANSP

57066a; plate 4; Pilsbry, 1940: fig. 384-1 - see image, above, left). Also see:

Compendium of

Daedalochila type material - a pictorial gallery (page one)

Among historic experiences in field biology, this Spring,

2007 expedition to a place less than an hour distant may be a bit on

the mundane side, but to the two of us it was a triumph. Doing our

homework, braving the hazards of snake envenomation, and exercising

a modicum of tenacity paid off. A piece of Thomas Say's legacy is

reawakened after nearly two centuries of quiet repose, and we 21st

century "pioneers" experienced the hunt, with all its passion and

suspense, while executing a well-reasoned game plan.

Binney, W. G. 1858. The complete writings of Thomas Say on the

conchology of the United States. H. Bailliere Co., New York. 1- 252

+ 75 plates.

Binney, A. [ed. A. A. Gould], 1857. The terrestrial air-breathing

mollusks of the United States and the adjacent territories of

North America. vol. 3. Little Brown, Boston. pp. 6-40 + 84

pls.

Lee, H. G., 1976. Thomas Say America's first malacologist.

Shell-O-Gram 17(11): 1-3. November.

Pilsbry, H. A., 1938. The type of Polygyra Say. The

Nautilus 52(1): 22-24. July.

Pilsbry, H. A., 1940. Land Mollusca of North America north of

Mexico vol I part 2. Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia.

vi + 575-994 + ix. Aug. 1.

Say, T., 1818. Descriptions of land and freshwater shells of the

United States (cont'd). Journal of the Academy of Natural

Sciences 1: 276. May. [not seen; reprinted version in Binney,

1858 consulted; vide supra]

Weiss, H. B. and G. M. Ziegler, 1931. Thomas Say Early American

naturalist. Charles Thomas, Baltimore. xiv + 1-260 + 26 pls. |

On April 6,

2007 Ed Cavin and I (Harry Lee) set out to find an authentic specimen of the

type species of Daedalochila. We had a very specific quarry

in the cross-hairs - the snail that America's first native-born

conchologist named Polygyra auriculata, the Ocala Liptooth.

Say (1818: 276) wrote: "This curious species we found near St.

Augustine, East Florida, in a moist situation. They were observed in

considerable numbers ..." Say never illustrated his snail, but an

early engraving (Binney,

1857: pl. 47, fig. 1 - see image, left) was consulted. The text and figure gave us a bit of reassurance for the

feasibility of our mission, but, after nearly 200 years, we expected

to encounter a considerable loss of suitable habitat and other

environmental degradation. The expedition certainly wasn't a

pre-ordained slam-dunk. To improve our chances of success, a closer

look at the history of Say's discovery was in order.

On April 6,

2007 Ed Cavin and I (Harry Lee) set out to find an authentic specimen of the

type species of Daedalochila. We had a very specific quarry

in the cross-hairs - the snail that America's first native-born

conchologist named Polygyra auriculata, the Ocala Liptooth.

Say (1818: 276) wrote: "This curious species we found near St.

Augustine, East Florida, in a moist situation. They were observed in

considerable numbers ..." Say never illustrated his snail, but an

early engraving (Binney,

1857: pl. 47, fig. 1 - see image, left) was consulted. The text and figure gave us a bit of reassurance for the

feasibility of our mission, but, after nearly 200 years, we expected

to encounter a considerable loss of suitable habitat and other

environmental degradation. The expedition certainly wasn't a

pre-ordained slam-dunk. To improve our chances of success, a closer

look at the history of Say's discovery was in order.  the stretch of 208

from the Old City to Picolata. Accordingly we stopped the car at

fairly regular intervals along CR 208, debarking at whenever "a

moist situation" which seemed to have promise was seen. In the

course of three hours no less than ten stations were made. At one

station some dead shells were found (along with a well-nourished

Pygmy Rattlesnake), but none of the other stops produced any

specimens (of D. auriculata that is; a Water Moccasin was

encountered, however). In near exasperation, we returned to the one

productive spot and, after nearly an hour of searching - without

re-encountering the rattlesnake - a living specimen of the Ocala

Liptooth was found in the grassy swale bank along the road.

Measuring a little over a half-inch, this snail is included, along

with a dozen empty shells of its species, in the accompanying

montage of illustrations. We believe these shells qualify as

topotypes (specimens collected in the same place of the type lot), which

imparts a certain authenticity to their identity. Furthermore, they

are dead ringers for the lectotype, which Say brought back to

Philadelphia in the Spring of 1818 (ANSP

57066a; plate 4; Pilsbry, 1940: fig. 384-1 - see image, above, left). Also see:

the stretch of 208

from the Old City to Picolata. Accordingly we stopped the car at

fairly regular intervals along CR 208, debarking at whenever "a

moist situation" which seemed to have promise was seen. In the

course of three hours no less than ten stations were made. At one

station some dead shells were found (along with a well-nourished

Pygmy Rattlesnake), but none of the other stops produced any

specimens (of D. auriculata that is; a Water Moccasin was

encountered, however). In near exasperation, we returned to the one

productive spot and, after nearly an hour of searching - without

re-encountering the rattlesnake - a living specimen of the Ocala

Liptooth was found in the grassy swale bank along the road.

Measuring a little over a half-inch, this snail is included, along

with a dozen empty shells of its species, in the accompanying

montage of illustrations. We believe these shells qualify as

topotypes (specimens collected in the same place of the type lot), which

imparts a certain authenticity to their identity. Furthermore, they

are dead ringers for the lectotype, which Say brought back to

Philadelphia in the Spring of 1818 (ANSP

57066a; plate 4; Pilsbry, 1940: fig. 384-1 - see image, above, left). Also see: